Research

Soundscapes of the self

Creative and Critical Projects in Classroom Music: Fifty Years of Sound and Silence was published by Routledge in November 2020 as a celebration of the innovative work of John Paynter and Peter Aston. The purpose was to build on the main themes of this work: the child as artist and the process of making music. The intention was to integrate practical work with critical and analytical thinking and consider where the next fifty years might lead in terms of music making.

My creative project, Soundscapes of the Self, was discussed in this work. In response to Paynter and Aston, it explores the nature of sound, the importance of understanding that true listening is hearing with attention, and how to explore the process of creating a soundscape which has a personal meaning. It considers how sounds can evolve into a composition and how to use the technologies which we have available to us in order to do so.

Places and communities have long been defined visually, though there is an increasing interest in investigating our sonic environment. This encompasses a wide range of practitioners, from architects to ecologists, and sound artists and composers. Murray Schafer, a Canadian composer, was fascinated by the sonic environment and how we popularised the idea of the ‘soundscape’. He was especially interested in exploring how we could make sense of the sonic environment (see Schafer 1993). Now with the easier availability of technologies, this offers an accessible means of composing.

A soundscape can be designed by the composer to represent an experience, a memory, or to evoke a sense of place within a community. Creating a soundscape of the self enhances one’s understanding of personal space and identity.

The very nature of these compositions are an exploration of sound and silence, relying less on the use of repeated rhythms or melodic patterns. Critical to the making of a soundscape is a refocused approach to listening. We are surrounded by sound and don’t often take the time to listen or to ‘hear with attention’. The American composer Pauline Oliveros, pioneer in the development of experimental and post-Second World War electronic music, emphasised the importance of ‘deep listening’ which is:

Listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, one’s own thoughts as well as musical sounds. Deep listening represents a sense of heightened awareness and awareness to all that is there.

‘As a composer I make my music through Deep Listening.’

The central principle of this project was to encourage the pupils to develop the concept of listening as being ‘hearing with attention’. We often discard the sounds around us as being unimportant. In order to achieve a state of deep listening we have to be aware of and include everything.

Such a state was evocatively promoted by Oliveros as, ‘Take a walk at night, and walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears’ (1974, 5).

As a preliminary activity, the class were asked to sit quietly, closing their eyes to listen as deeply as possible to the surrounding sounds.

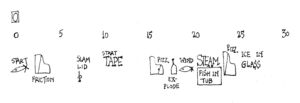

Upon a second time of listening, they were to make a note of the different types of sound that can be heard. These sounds were described in a table with reference to pitch, duration and timbre. Soundscapes of the self 30

Pupils were asked if they felt they could represent these sounds visually. A useful exercise was to look at examples of other graphic scores, to demonstrate how composers have notated their work, not in the conventional sense, but through imaginative visual description.

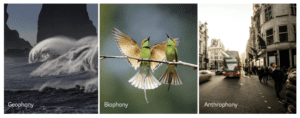

As a second preliminary activity, using the work of sound ecologists Gage and Krause (see, for example, Krause 2008) we considered how sounds might be classified in terms of the respective fields of Biophony (birds and animals), Geophony (non-biological natural sounds) and anthrophony all sounds produced by humans.

These terms are used by those working to understand the ways in which the interactions of humans in their environment impacted upon ecological conservation and so linked with aspects of other subjects which the pupils were studying and aware of. We discussed the sounds you might hear walking in town, if you’re near a train station, a cafe, the sounds of Ashridge forest.

The aim of this creative project was to create a soundscape unique and personal to you and where you live. You could take an aspect of your day, or surroundings and document these, and create a composition from these elements. The pupils experimented first with taking a sound walk, to identify and record interesting sounds. Some chose to make an audio narrative of a specific place, simply by choosing a location and then leaving the recording running for a minute. They created a musical scrapbook of sound taking recordings from a variety of places. Working in pairs, sounds were selected with consideration to a variety of pitch, duration and intensity.

It was lovely to see the enthusiasm of the pupils who would come back having added to their sonic scrapbook, describing the sounds they had heard and how it could work in their composition.

There are different ways of approaching the compositional process. The collected sounds could be reproduced vocally or on instruments, or input into a computer programme, of which there are various examples. Different tracks can be produced and layered, or the sounds modified and altered, (for example, by time stretching particular sounds). Alternatively, the use of recorded 31 BIO Micheila Brigginshaw is a musician and teacher of music. She is passionate about the power of music to inspire creativity and enable one to reach their full potential. She has worked at Berkhamsted School as a classroom and piano teacher since 2010. Micheila became interested in the writings of Pauline Oliveros, the development of soundscaping in the work of contemporary composers and the way in which that offered an accessible means of composing in the classroom. This led to further research and publication of an essay in Creative and Critical Projects in Classroom Music, published by Routledge in November 2020. Micheila continues to research in this field. This subject and the importance of ‘listening with attention’ remains a source of fascination for her. sound could be combined with other instruments, or the discovered sounds could be the inspiration for an instrumental or vocal composition.

Emily, investigating her school environment, used recordings including corridor chatter, school bell, the sound of writing, and a teacher giving instructions to the class. Her composition opened with the sound of the school bell amidst indistinct chatter and footsteps over a repeated four chord pattern. This was looped to provide a hypnotic accompaniment to her soundscape. This track segued into the sound of the teacher’s voice and then to the sound of writing. The latter had a distinctive rhythmic quality and was layered to build intensity and exploit this. The bell interrupts this sequence and leads back to the opening chatter at a higher volume than before. The sound of writing, on a single track this time, but stretched to distort the sound, was used, juxtaposed with the sound of a cough, then a sigh. A final bell rings and the four chord accompaniment plays out to fade.

How do we become better listeners in a world dominated by visual stimuli while being surrounded by sounds we may not notice? Pupils were encouraged to consider how, as a part of this process, they might listen to their environment in a different way and be more mindful of the sounds by which they are surrounded. For further ideas about listening, investigate Pierre Schaefer’s theory of listening modes (see, for example, Kane 2014, 15-41). He described the ideas of ‘reduced listening’ in which he identified the musicality hidden within commonplace sounds, complex rhythms, interesting textures, or tonal qualities.

Other useful ways to research would be to listen to examples of this process in other composers. Deserts (1950-4) by Edgard Varèse in which sequences of ‘organised sound’ on tape are interwoven into a composition for an orchestra of wind, piano, and percussion. The melodic content of Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988) is based on the contour and rhythm of ordinary human speech. Many composers have been passionate lovers of nature and show this in their work.

Many of Beethoven’s were inspired by his long walks, including the Pastoral Symphony. Much of the music of Claude Debussy evokes the natural world in some form, and he was passionate about the symbiosis between music and nature, capturing the essence of landscapes and the drama of nature in works such as Les Collines d’Anacapri and La Mer. The influence of nature could be explored in the works of other composers, such a Messaiens’s depiction of birdsong in his magnum opus Catalogue d’Oiseaux and Jonathan Harvey’s Bird Concerto with Pianosong, scored for solo piano, instrumental ensemble, and electronic and computerised hardware. Lucy Claire, with her beautifully evocative soundscape compositions, notes how ‘Music is everywhere! It is in the whoosh of the wind, the patter of the rain, the rhythm of a train and the ding of a bell’ (see: <www.lucy-claire.com>).

As an extension to this project, could there be a way of creating a record over time of one’s own personal sound ecology and environment? Soundscape compositions, by their very nature, allow the listener to become immersed in the physical environment of a place, highlighting the ecology of the setting. This idea, in 2020, fifty years on from the publication of Sound and Silence, has been brought into sharp focus with the drastically altered sonic environments across the globe. Sound ecologists are mapping the world, creating a shared audio landscape. For example, the fascinating work on the site of ‘Cities and Memories’ by Stuart Fowkes (<www.citiesandmemory.com>), which explores the unique sounds of different areas, cities and natural sites, and creatively reimagines them, creating unique sounds with an innovative use of technology.

John Paynter writes in Hear and Now: an introduction to modern music in schools that ‘Music is about getting excited by sounds’ (1972, 7-14). There’s not such a big gulf between the music of today and the music of the past. In fact, there’s no gulf at all. All that has happened is that resources have increased. There are now more sounds to be used for making music and more ways of using them. Find some sounds and start making music.